IT WAS Emily Dickinson's birthday the other day. I know this because 10 December's Poem of the Day was Emily's strange and strangely wonderful poem, This World is not Conclusion.

What am I saying? It's not just This World is not Conclusion which is strange and strangely wonderful. Each and every poem by Emily Dickinson poem stays with you for its oddly direct and sensual phrasing.

Emily Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on 10 December 1830. Her writing was not much known when she was alive as, by the time she died on 15 May 1886, only ten poems had been published out of cache of nearly 2000.

She never married and as she moved through her life, became an increasingly reclusive character, living mostly through the written word via letters to friends she had mostly never met.

Perfect for a poet. She'd have loved the digital age, I’m sure of it.

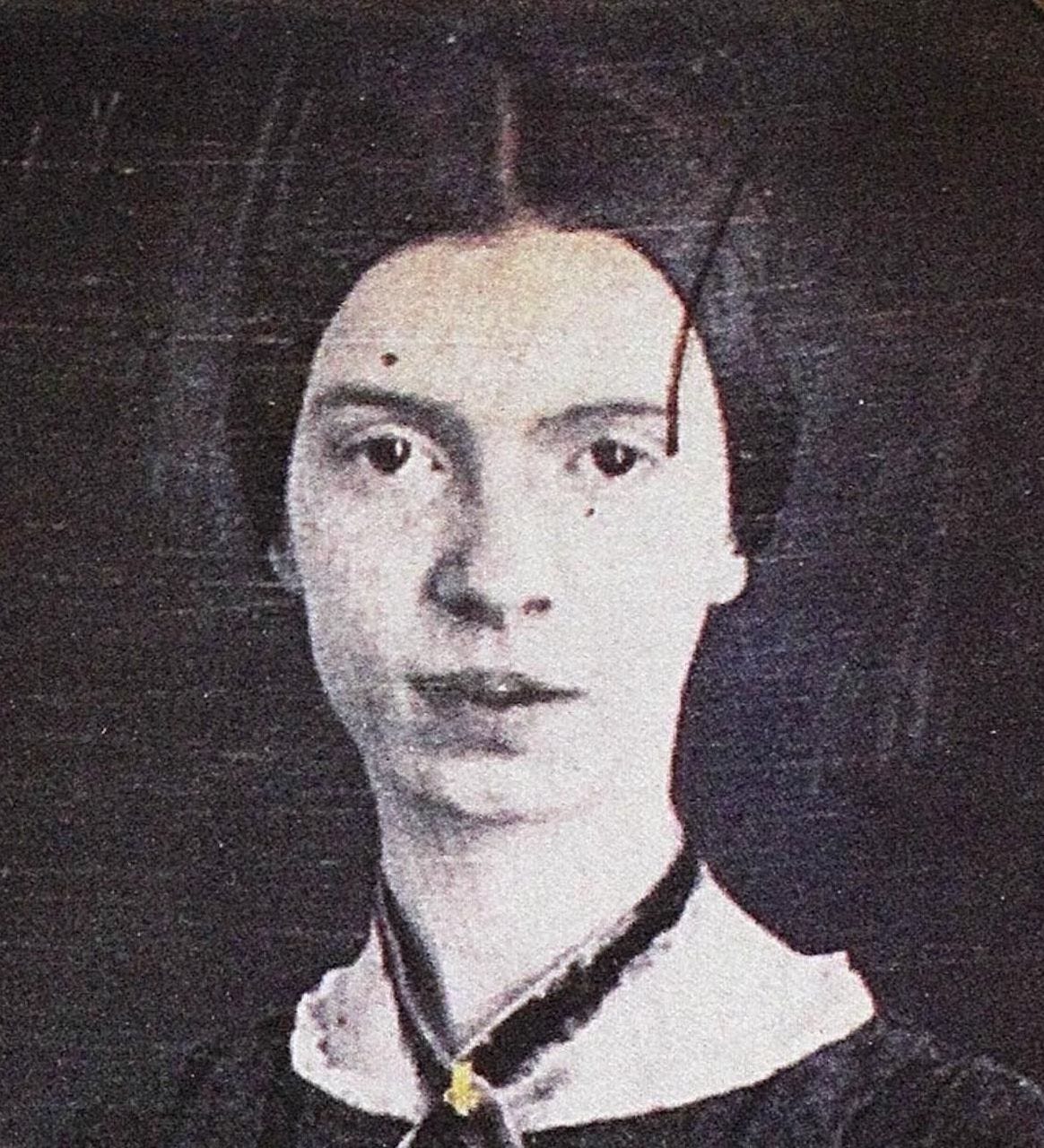

Once, in response to a request for a photograph from one of these regular correspondents, T.W. Higginson, Emily responded:

I . . . am small, like the Wren, and my Hair is bold, like the Chestnut Bur—and my eyes, like the Sherry in the Glass, that the Guest leaves.

Like many poets, Emily Dickinson was drawn to subjects such as love, death, spirituality, immortality and the natural world.

That old poetic favourite, mutability, was also high on her agenda.

This is the poem which woke me up with a jolt on the morning of her 196th birthday.

This World is not Conclusion

This World is not Conclusion.

A Species stands beyond -

Invisible, as Music -

But positive, as Sound -

It beckons, and it baffles -

Philosophy, dont know -

And through a Riddle, at the last -

Sagacity, must go -

To guess it, puzzles scholars -

To gain it, Men have borne

Contempt of Generations

And Crucifixion, shown -

Faith slips - and laughs, and rallies -

Blushes, if any see -

Plucks at a twig of Evidence -

And asks a Vane, the way -

Much Gesture, from the Pulpit -

Strong Hallelujahs roll -

Narcotics cannot still the Tooth

That nibbles at the soul -

Emily Dickinson

(December 10th 1830 – May 15th 1886)

The footnotes in Poem of the Day One & Two books are always illuminating.

This is what the editor's notes say against 10 December in Book One:

Dickinson described her art with typical, striking economy: "If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold I know no fire can ever warm me, I know it's poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way?"

Without connection, there is no meaning

As someone who writes about art, I have thought a lot about what it is which makes people connect with art. Be that the written, or spoken word, visual art or music.

In these four brief lines, Emily pins it down. All artists strive to make a connection with the beholder. Without connection, there is no meaning.

An example. In late 2013, I went to see an exhibition of Louise Bourgeois' work at Edinburgh's Fruitmarket called I Give Everything Away.

This French-born artist, who died in 2010 at the age of 98, only gained recognition late in life when she was reached her seventies.

Before I went to see I Give Everything Away, I visited that year’s big summer blockbuster exhibition, devoted to Scots-born painter Peter Doig, in the National Galleries of Scotland.

I recall a lot of excitement around the show. Although he left Scotland as a child for Canada, we like to claim Doig as our own. Famous for portraying lonely figures in empty land or seascapes, his work sells for a LOT of money, In 2007, White Canoe, an atmospheric painting of a moonlit lagoon, sold for £5.7m. At that time, a record figure for a living European artist.

I remember feeling deflated by the Doig show. I was with a painter friend that day. We both felt it.

Louise Bourgeois changed our mood completely. Especially a group of large works on paper, I Give Everything Away, made by Bourgeois in the year leading up to her death.

The feeling I had in my body when I started to look at these etchings was as Emily Dickinson described. A bone coldness followed by a flush in my head – not unlike the overused Emoji which depicts the top of a head blowing off.

I hardly knew which one to look at first, but one in particular drew me to it. The right hand side of the picture showed a blood red flower which could be taken for a heart, underpinned by a wave of pale blue which curving around its root.

In the left hand side of the etching, in pencil, Bourgeois had scrawled the words, 'I leave my home'.

Part of my unconscious brain, which a couple of years earlier had tearlessly closed the door for the final time on my late mother's home, finally caught up with the rest of me.

The finality of a life ending. The leaving of a newly emptied family home; like a reversal of the birth process. These are universal themes everyone faces in the course of a lifetime, but somehow Louise Bourgeois had crystallised the whispering of emotion I'd consigned to a box in my head marked 'too difficult'. And she'd done it with in one simple image.

All great artists, like Emily Dickinson and Louise Bourgeois, cut to the quick of human experience with a single deft line.

This afternoon, I looked out my midwinter window to see tall Caledonian Pines and bare birch trees wave and block a mottled rose pink sky. Another short day ends. The feeling of pervasive melancholy which stalks this time of year was given a name in Emily’s poem, There's a certain Slant of light.

When it comes, the Landscape listens –

Shadows – hold their breath –

For more background on my poetry habit, see my previous Airts & Pairts post, See Me

I remember that Louse Bourgeois show well too - especially the hundreds of red biro ‘insomnia’ drawings she made. But isn’t it just so very tiresome that women artists have to outlive all their male contemporaries before anyone will take them seriously? It’s a pattern we see again and again…

and thank you for sharing Emily Dickinson’s words. Perfect.

A very moving, well-crafted, piece, Jan, thanks! Passed some of that landscape today by train: reading poem after poem until the sun's abrupt demise...