Rediscovering a 'lyrical painter, whose colour is like a musician's sound'

The life and work of Alasdair Taylor

During a couple of stints in BBC Scotland’s press office I was always tickled when we used the phrase another chance to see in press information – largely tongue in cheek – instead of repeat. But here I am, dear reader, just a couple of months into Substacking and I’m offering you another chance to read, in the shape of a newly edited piece I wrote last summer about overlooked Scottish artist Alasdair Taylor (1936 – 2007).

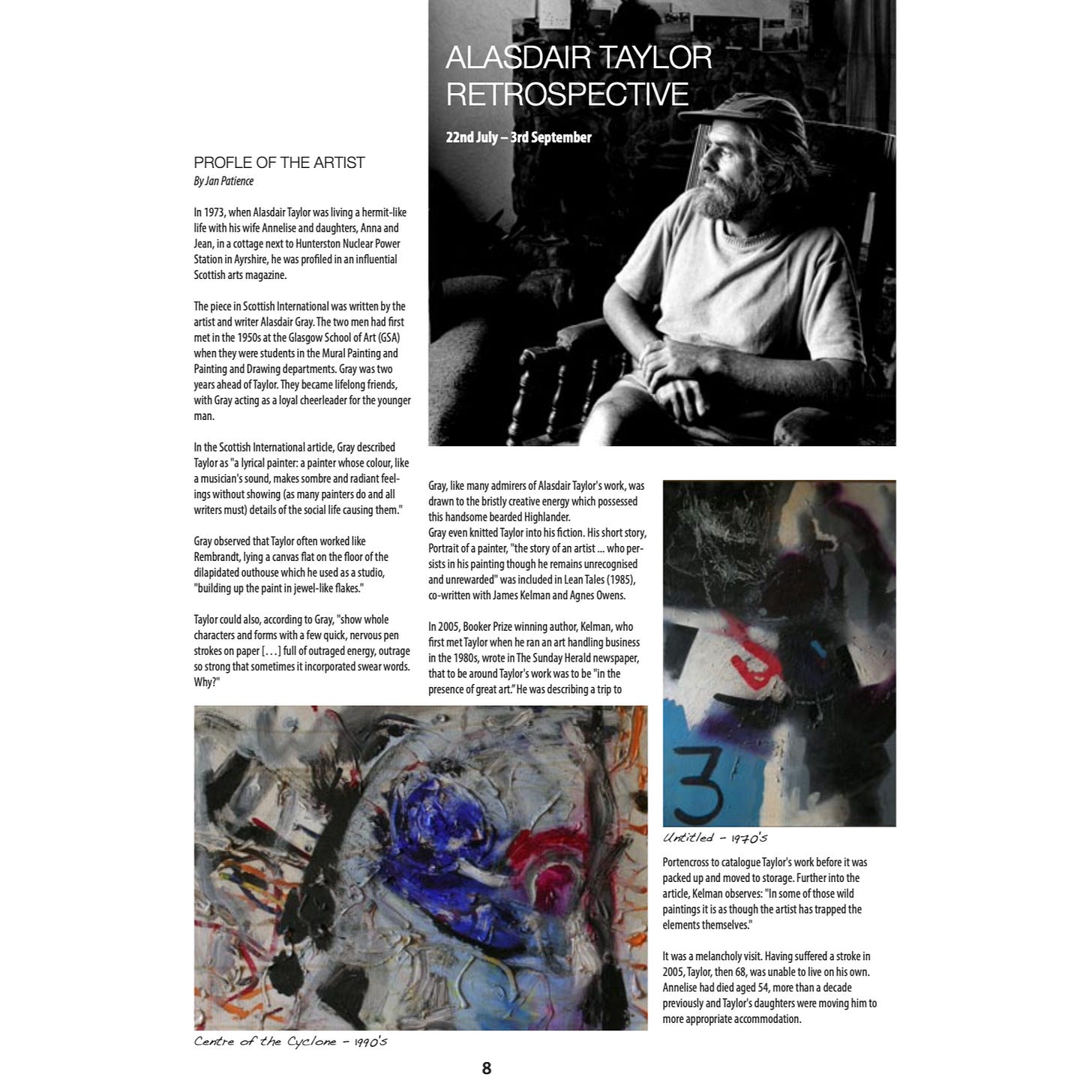

I’m taking a punt that most of you didn’t read it, as it appeared in a magazine produced by the Friends of the Maclaurin to promote arts in South West Scotland. Alasdair Taylor was the subject of a large retrospective at the Maclaurin Art Gallery in Ayr last year. It was a cracking show, tracking Taylor’s artistic development through his paintings, sculpture and archival material, over five decades. From his time at Glasgow School of Art in the 1950s up to his death in 2007, at the age of 70.

He was an artist who always worked at full throttle; chopping, changing, experimenting in the uncompromising way that true artists do. In later life, despite the best efforts of supportive and admiring pals, such as Booker Prize winning author, James Kelman, and artist, writer and all-round polymath, Alasdair Gray, he preferred to create away on his own at his remote cottage in north Ayrshire.

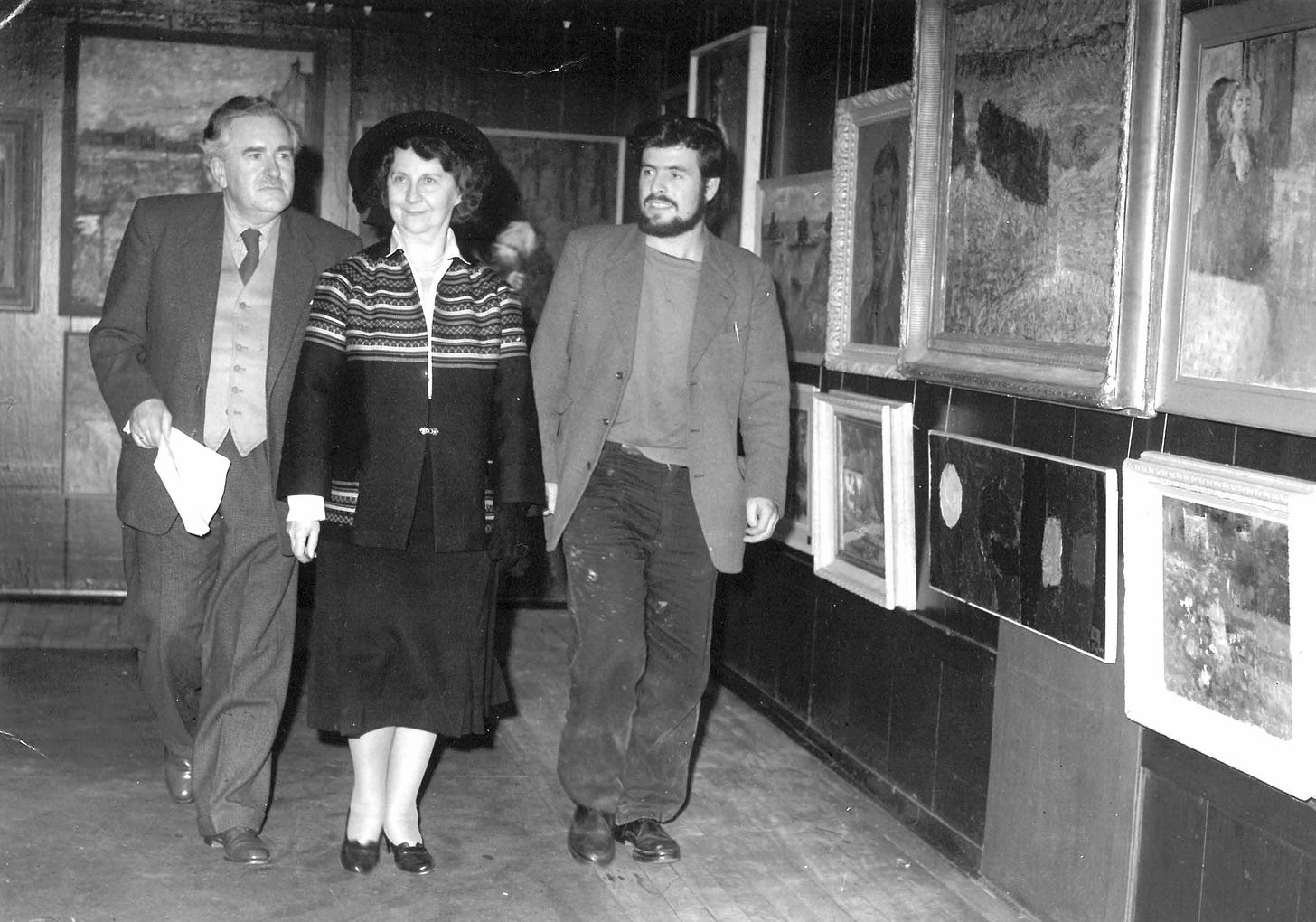

At art school, Alasdair was one of these stand-out students we probably all had in our class. The One Most Likely to Succeed. A degree of critical success and media attention came a-calling for him as a young man. There were numerous reports in newspapers and magazines of the day about Taylor and his work, radio appearances and even a BBC Scotland Scope documentary in 1974 showing him at his home studio by the critic and broadcaster, W. Gordon Smith.

The film showed Alasdair painting one of his spray paint artworks flat on the floor of his studio. Take that Banksy…

By then, he was in his orange and purple phase. In 1975, he took a leaf out of the Beatles playbook and spent six weeks to the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (later called Osho) Ashram Meditation Resort in Pune, western India.

Gradually, Alasdair slipped off the radar of all but a few close friends in his tight artistic circle. Playing the art world game can sap a creative soul. In my mind, Alasdair Taylor was a one-off. As most true artists are. I hope you enjoy reading the following as much as I enjoyed delving into his life and work…

ALASDAIR TAYLOR: HIS LIFE & WORK*

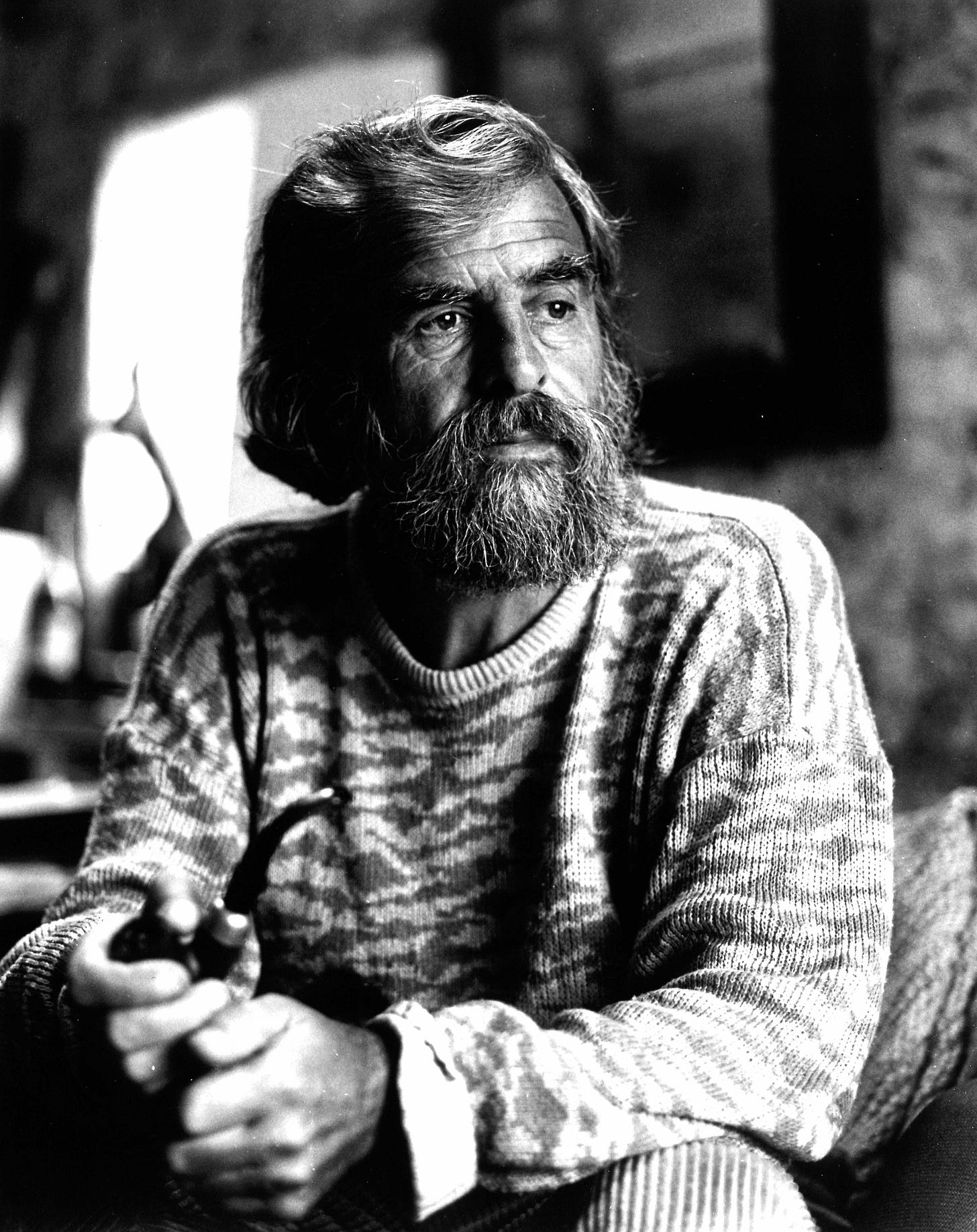

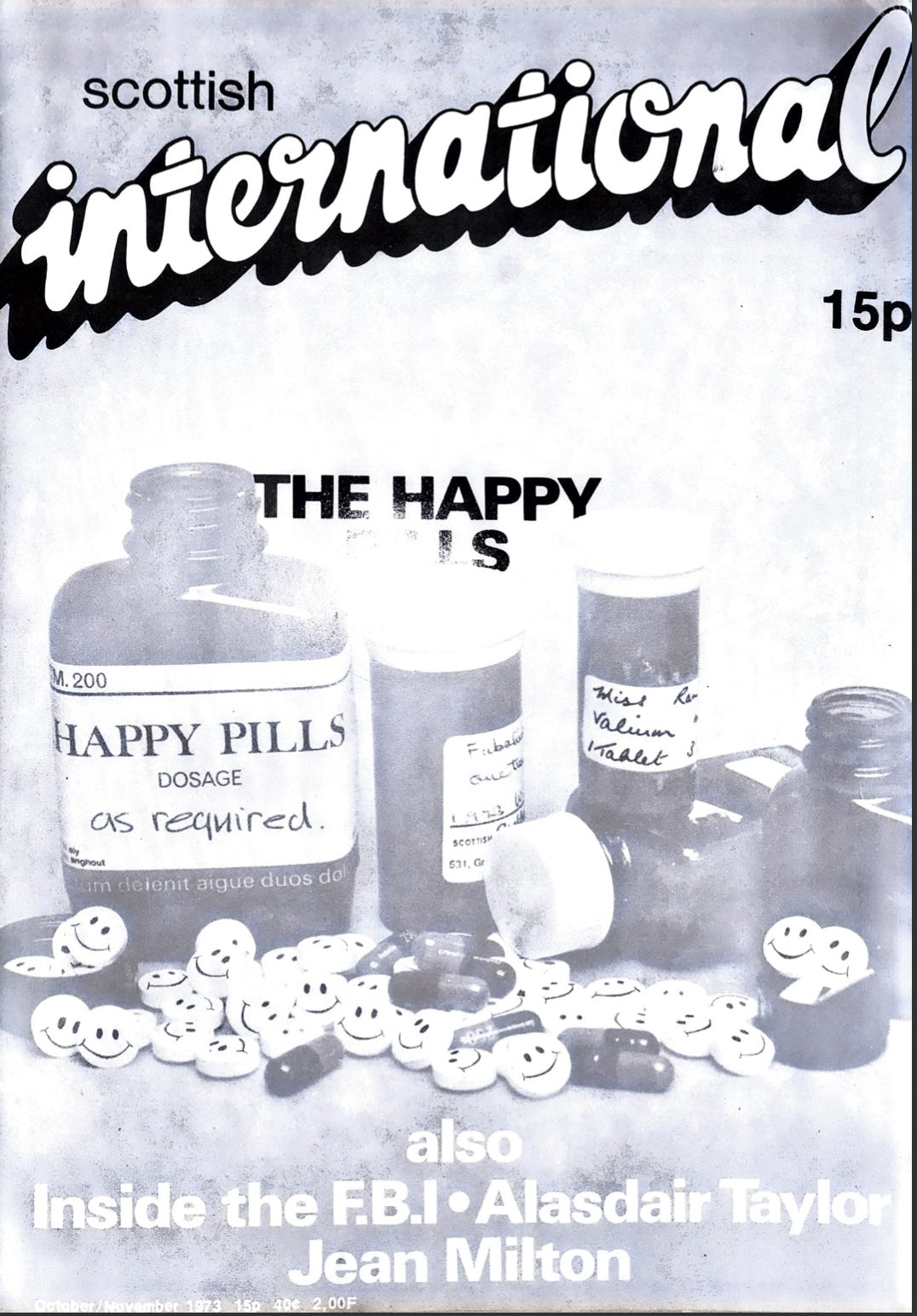

In 1973, when Alasdair Taylor was living a hermit-like life with his wife Annelise and two young daughters, Anna and Jean, in a cottage next to Hunterston Nuclear Power Station in Ayrshire, he was profiled in an influential Scottish arts magazine.

The piece in Scottish International was written by his friend, the artist and writer Alasdair Gray. The two men had first met in the 1950s at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA) when they were students in the Mural Painting and Painting and Drawing departments. Gray was two years ahead of Taylor. They went on to become lifelong friends, with Gray acting as a loyal cheerleader for the younger man.

In the Scottish International article, Gray described Taylor as “a lyrical painter: a painter whose colour, like a musician's sound, makes sombre and radiant feelings without showing (as many painters do and all writers must) details of the social life causing them.”

Gray observed that Taylor often worked like Rembrandt, lying a canvas flat on the floor of the dilapidated outhouse which he used as a studio, “building up the paint in jewel-like flakes.”

Taylor could also, according to Gray, “show whole characters and forms with a few quick, nervous pen strokes on paper […] full of outraged energy, outrage so strong that sometimes it incorporated swear words. Why?”

Gray, like many admirers of Alasdair Taylor's work, was drawn to the white heat of creative energy which possessed this handsome bearded Highlander.

He even knitted Taylor into his fiction. His short story, Portrait of a painter, “the story of an artist ... who persists in his painting though he remains unrecognised and unrewarded” was included in Lean Tales (1985), co-written with James Kelman and Agnes Owens.

In 2005, Booker Prize winning author, Kelman, who first met Taylor when he ran an art handling business in the 1980s, wrote in The Sunday Herald newspaper, that to be around Taylor's work was to be “in the presence of great art.”

He described a trip to Portencross to catalogue Taylor's work before it was packed up and moved to storage. Further into the article, Kelman observed: “In some of those wild paintings it is as though the artist has trapped the elements themselves.”

It was a melancholy visit. Having suffered a stroke in 2005, Taylor, then 68, was unable to live on his own. His wife, Annelise, had died aged 54, more than a decade previously, and Taylor's daughters took the difficult decision to move him to more appropriate accommodation.

Alasdair died on January 1 2007, at the age of 70.

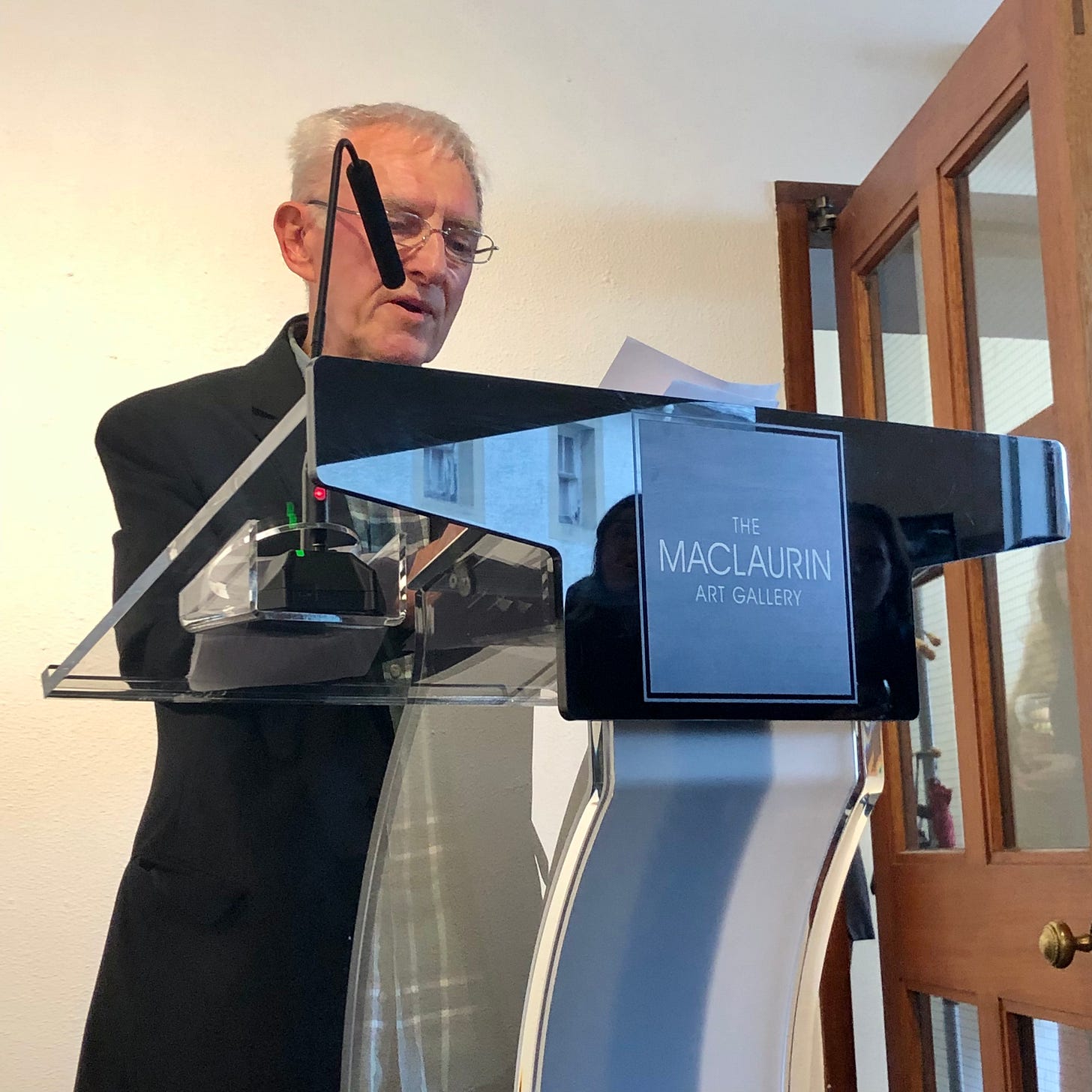

Despite having prominent cheerleaders, including Jim Kelman calling for a major retrospective of his work in 2005, apart from a small survey of his work at Irvine's Harbour Arts Centre in 2007, it took 16 years for such a show to take place; in the summer of 2023 at the Maclaurin Art Gallery in Ayr. This wide-reaching retrospective of Alasdair Taylor's vast artistic output was opened by Kelman, who said of his old friend:

“Alasdair Taylor painted and worked as the whole person, he worked at full pitch, that was how he worked; this is a mark of greatness that I see, each day an advance on the one before, that entire 24 hour period, all of the experiences and phenomena that this entails, it is there in what it takes to continue the work, all of the emotional peaks and troughs, and for Alasdair this too was an aid to survival, if not a life-saver, and he continued working, making what he could of it.”

Taylor's desire to create saw him working on every surface, from newspaper, to canvas, stone, railway sleepers, discarded theatrical backdrops or old baker's boards salvaged from the beach near his home.

His vision was wholly his own. Friends, including Alasdair Gray often observed that his approach to making art always had the instinctive spontaneity of a jazz man – which he was. He was also a nifty footballer.

Alasdair Grant Taylor was born in Edderton, near Tain in Ross-shire in December 1936. His father, Hugh, was stationmaster at the local train station. His mother, Jane, a primary school teacher, was also a talented pianist who played in a small dance band which entertained troops home on leave. At the age of seven, her son began to accompany her on the drums.

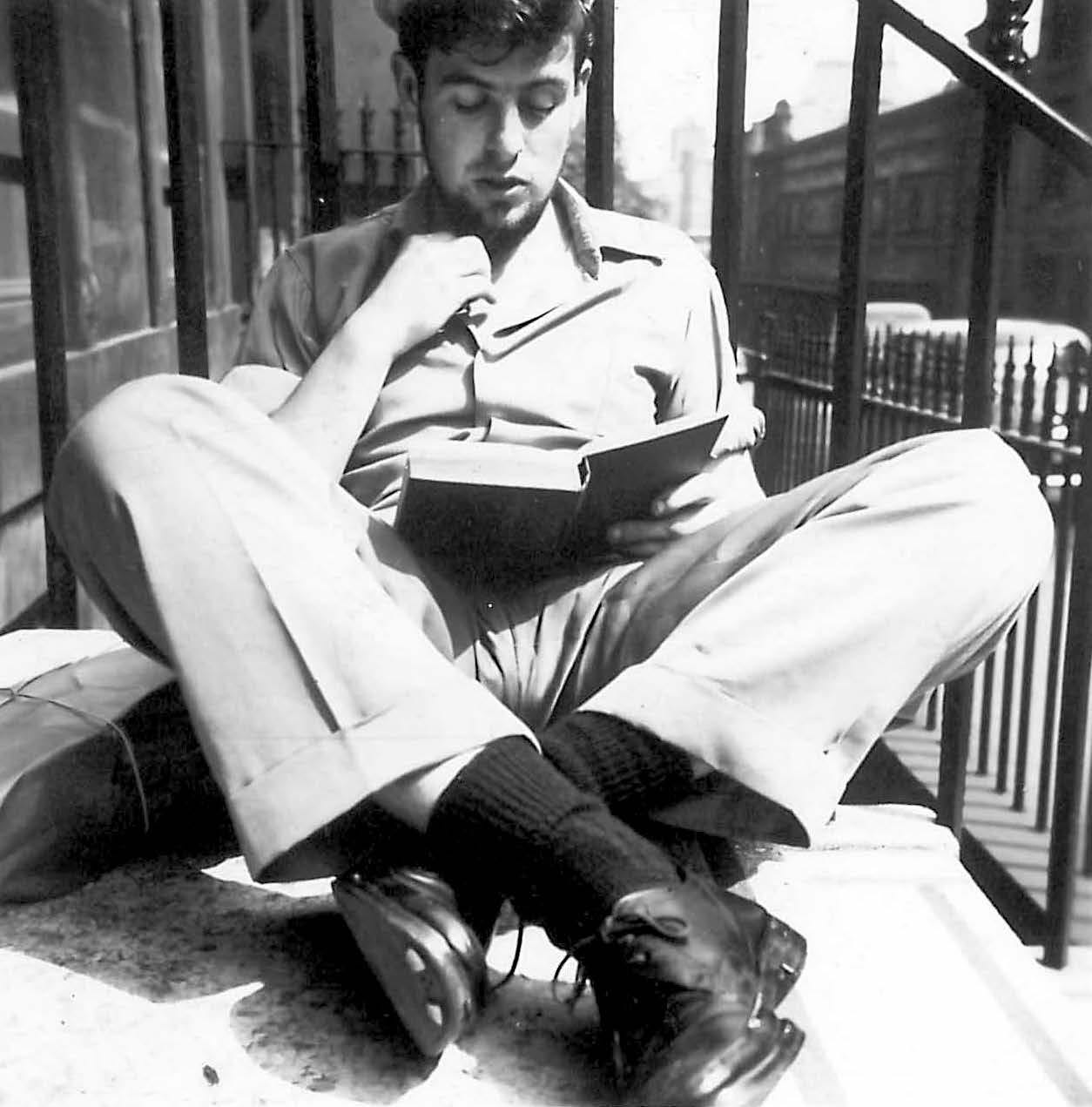

In 1946, the Taylors moved to Coalburn, Lanarkshire. Alasdair drummed with bands while at school and, when he moved on to art school in Glasgow from 1955 to 1959, played in the art college's jazz band.

Taylor was also involved in GSA's Student Christian Movement. According to Gray, he flirted with the idea of becoming a monk, even travelling to a monastery in England to investigate the possibility. The heavily regulated, ascetic life a monk was not for the free-spirited Taylor, but he maintained a lifelong interest in spirituality and mysticism. In the 1970s, he even went to India to explore this further.

It all fed into his art.

In 1958, in his penultimate year at GSA, Taylor visited London to look at Rembrandt's Madonna and Child paintings. This led to a coup de foudre when, sitting in art house cinema, The Academy, on Oxford Street, watching films about Rembrandt, Michelangelo and Piero Francesca, he spotted a beautiful girl.

Years later, recalling this first meeting with Annelise Marquard during an interview with W. Gordon Smith for a Scope documentary on BBC Scotland, Taylor explained:

“There were around seven people in the cinema, and there was this blonde girl sitting about four rows away, and I had to speak to her […] so I followed her up the street. We talked. We went to the British Museum. I found the original Madonna and child drawings by Rembrandt and we sat with guards round them and drew them.”

The pair went on impromptu trip around the Highlands, causing alarm at the art school in Glasgow, that this talented student was not coming back to complete his diploma.

Taylor made it back in the nick of time, winning the prestigious Governor's Prize for his painting, The Expulsion of Eden, which featured Annelise.

After graduation, having sold his drum kit and with £50 in his back pocket from winning the Governor's Prize, Taylor headed for Silkeborg, in central Denmark, to seek out Annelise. Despite opposition from her parents, horrified that a bearded, kilted Scotsman had turned up on their doorstep looking for their daughter, the couple married.

The couple spent a year in Silkeborg and through Annelise, Taylor met Asger Jorn, a member of the CoBrA group of artists. Jorn exemplified the group's highly expressionist painting style, inspired by the spontaneity of children's art. Taylor absorbed these innovative techniques like a sponge.

The couple returned to Glasgow in 1960 and Taylor spent a miserable month teaching before taking up a job as a bin man with Glasgow Cleansing Department. Their next move, some six months later, was into the University of Glasgow's Chaplaincy Centre where Alasdair had been appointed caretaker. This allowed him to concentrate on his art, while Annelise served food and drinks to students.

The Taylors spent five years at the Centre. Their daughter, Anna, was born in 1960, followed by another daughter, Jean in 1963. In late 1965, the family moved to Northbank Cottage, on an isolated promontory near Portencross in north Ayrshire.

Despite the lack of electricity and basic amenities, the cottage suited the young couple. They were charged a peppercorn rent to keep an eye on the landlord's potato fields. It also meant Alasdair could make work for various exhibitions in the outbuildings surrounding the 300-year-old cottage.

Ever-resourceful and a creative powerhouse who kept the family going through lean times, Annelise took on part-time roles at various local schools and community schools.

Exhibitions came and went and critics came calling. In a half-hour-long arts documentary which aired on BBC Scotland in 1974, Taylor was filmed in and around Northbank. One scene shows him almost in a trance-like state, talking as he worked on one of his distinctive car-spray paintings laid out on the floor.

Later, during a revealing face-to-face discussion with the presenter, Taylor admits to 'a feeling of failure' as Annelise had recently become main breadwinner for the family. Taylor is also asked if he thinks society owes artists a living. He ruminates before conceding: “I am not very good at being business-like in an economical sense.”

This comment about the economics of the art world art hid another aspect of Taylor's views on creating art. According to his daughters, he thought of his paintings as being 'like children' and didn’t actively try to sell them.

Great art goes beyond hard cash. It touches people. And now his daughters want the wider world to know about their father's art and to feel its power. The Maclaurin retrospective, planned before the pandemic, was a monumental undertaking for Alasdair's family.

The late Celia Stevenson, a powerhouse of creative energy herself, who worked tirelessly behind the scenes at The Maclaurin for many years, also helped make the retrospective exhibition a reality.

This wide-reaching survey demonstrated the progression of his art over 50 years, as he moved restlessly into different stages and between styles.

As Jim Kelman said in his closing remarks when he opened the retrospective:

“It takes a huge act of faith to struggle and fight through the years, as Jean and Anna have done, given the moments of doubt that there must have been; as always there are for the family of an artist whose work is barely acknowledged beyond a small circle of people. Alasdair was their dad, of course he was, but it was his work that was special, that needs to be encountered, needs to be seen.

“They stuck with it, trusting their own judgment, keeping faith in the own judgment and understanding of what art is, and what great art can be.”

Alasdair Taylor's art is bold, spontaneous and free-spirited. It pulls you in and occasionally spits you out. It conceals more than it reveals. Above all, it demands to be seen.

Hi Jan. Thanks for giving us a chance to revisit your article !! I wish I’d seen this show. This wonderful artist with film star looks deserves better attention. G